|

| Detail of the Padampa lineage painting, +1 level - click to expand - © Sotheby's Today we will continue from the last blog where we talked about the content of the middle register with its central figure being none other Padampa himself. Now we proceed to move gradually, one level at a time, upward to see who among the Indian teachers of Padampa we may encounter there. Above you see six circles (go ahead and download it so you can see the details), each enclosing a group of Padampa’s teachers. If you look closely you will see that the first and last of the six circles contain 5 female figures each, while the four middle circles (the 2nd through the 5th) each contain 11 male figures. Each circle includes a central figure, and the identification of the central figure gives us a key to identifying the group of persons depicted around them. The total number of figures depicted here adds up to 54, which is the correct number for the frequently mentioned group of “54 male and female common siddha teachers of the authorization transmissions” (thun-mong lung-gi bla-ma grub-thob pho mo lnga-bcu-rtsa-bzhi). The word ‘common’ here just means that these teachers were not uniquely Padampa’s but had other students as well. It does not mean ordinary. If you remember, we have a Dharmaśrī text (Dh) that gives a more detailed version of the earlier Jamyang Gonpo text (JG). Both texts treat this as a lineage tree visualization, with the meditator at the center, although they are different in their order, creating a mild and not-all-that lethal confusion. Like our two authorities, we will save the women teachers for later, and start with the 2nd circle. JG says that to the meditator’s back is a group of eleven lamas for the knowledge of philosophy and grammar made up of Klu-sgrub-snying-po and so on. JG has no full listing of names, but this is supplied by Dh. I’ve added what I believe to be the correct Sanskrit forms of the names, although not always with the kind of complete confidence that might be desired by some of you: |

[D1] Klu-sgrub-snying-po. Nāgārjunagarbha or Nāgārjunasāra.

[D2] Shes-rab-bzang-po. Prajñābhadra.

[D3] Yon-tan-'od. Guṇaprabha.

[D4] Chos-grags. Dharmakīrti.

[D5] Ā-ka-ri-siddhi. Ākarasiddhi.

[D6] Shangka-ra. Śaṅkara.

[D7] Ye-shes-snying-po. Jñānagarbha.

[D8] Thogs-med. Asaṅga.

[D9] Ārya-de-ba. Āryadeva.

[D10] Zhi-ba-lha. Śāntideva.

[D11] Gser-gling-pa. Suvarṇadvīpin.

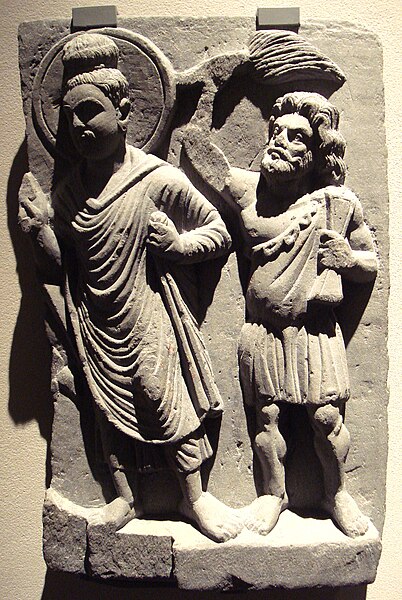

Klu-sgrub-snying-po is none other than the Nāgārjuna figure with the multiple snakes forming a cover over his head (look closely and you will see them) in the center of the 2nd circle.

If the next group (the 3rd circle) is not at all clear in the painting, we may nevertheless surmise that it must be the group centered on Saraha. He is not often depicted without an arrow, and you don't see any arrow held by any of the other central figures, so this group must be his. (I hope you followed this somewhat tortuous logic. Anyway, the seating posture appears to be the one usually adopted by Saraha.) Here is Dh's listing of the group visualized in front of the meditator, the eleven lamas of the symbolic [transmission of] Great Sealing:

[A1] Sa-ra-ha. Saraha.

[A2] Tsārya-pa. Caryāpa.

[A3] Gu-ṇa-ti. Guṇati?

[A4] Tog-tse-pa. Kuddāla.

[A5] Ko-ṣha-pa. Koṣapa?

[A6] Sha-ba-ta. Śabari?

[A7] Mai-tri-pa. Maitripā.

[A8] Phā-ga-ra-siddhi. Sāgarasiddhi.

[A9] Nyi-ma-sbas-pa. Ravigupta.

[A10] Ā-ka-ra-siddhi. Ākarasiddhi.

[A11] Ratna-badzra. Ratnavajra.

With only two remaining, it might seem a problem to decide which is which, but I believe the group centered around Buddhaguhya must be the one represented in the non-tantric style, while the one circled around the portly yogi must be the one centered around Saroruhavajra (Mtsho-skyes-rdo-rje), the Hevajra Tantra author, and Hevajra is usually regarded as a Mother Tantra. So the group in the 4th circle must be the one that includes these persons listed in Dh, visualized to the meditator’s left side. They are called the 11 lamas of the Mother Tantra experience of bliss (ma rgyud bde ba nyams kyi bla ma bcu gcig):

[C1] Mtsho-skyes-rdo-rje. Saroruhavajra.

[C2] Indra-bhū-ti.

[C3] Ḍombhi-pa. Ḍombipa.

[C4] Rdo-rje-dril-bu-pa.

[C5] Ti-li-pa. Tilopa.

[C6] Nag-po-zhabs.

[C7] Sgeg-pa-rdo-rje. Lalitavajra.

[C8] Lū-i-pa.

[C9] Bi-rū-pa. Virūpa.

[C10] Kun-snying (i.e., Kun-dga'-snying-po). Ānandagarbha.

[C11] Ku-ku-ra-pa.

The 5th circle contains the group headed by Buddhaguhya. Its members are listed by Dh under the descriptive name “the 11 lamas of the Father Tantra winds of motility.”

[B1] Sangs-rgyas-gsang-ba. Buddhaguhya.

[B2] Padma-badzra. Padmavajra.

[B3] Ngag-gi-dbang-phyug.

[B4] Go-dha-ri. Godhari? Elsewhere spelled Gu-bha-ri and Ghu-da-ri-pa.

[B5] Karma-badzra. Karmavajra.

[B6] Dza-ba-ti.

[B7] Ye-shes-zhabs. Jñānapāda

[B8] Klu-byang. Nāgabodhi.

[B9] Swa-nantā. Ānanda?

[B10] Kṛṣhṇa-pa.

[B11] Ba-su-dha-ri.

Now for the group of 10 women teachers divided between the first and last circles. I have no iconographic means to distinguish which is which at the moment, so I will just list them as one group. They are called “the ten skygoers who are lams of direct introduction to awareness” (mkha' 'gro ma rig pa ngo sprod kyi bla ma bcu):

[E1] Ḍā-ki Su-kha-siddhi. Sukhāsiddhī.

[E2] Ri-khrod-ma. Śabarī.

[E3] Padmo-zhabs. Padmopāda?

[E4] Ku-mu-da. Kumudā.

[E5] Bde-ba'i-'byung-gnas. Sukhākara.

[E6] Ganggā-bzang-mo. Gaṅgābhadrī.

[E7] Tsi-to-ma. Cintā.

[E8] La-kṣhi-ma. Lakṣmī.

[E9] Shing-lo-ma. Parṇā?

[E10] There ought to be ten in the list, but I can only count nine. The missing one would be Dri-med-ma. In Sanskrit, Vimalā.

Oh my sore back! We’re not nearly done yet with the upper part of the painting, and I’ve already gotten tired. It was a lot more work than I had thought it would be, and I’m not sure how much you are really appreciating it. I can hear some people saying, ‘Too much information already!’ Let me just put off the rest for now and take a short rest.

At least we’ve gotten through one more very significant part of the painting and identified the figures that are included in the six circles immediately above the figure of Padampa. This is the main group of his Indian teachers according to the sources. If you want to know whether Padampa met these teachers in the flesh or in vision (some, like Saraha, surely must have lived long before him), I don’t have much of an answer that would satisfy everyone. Perhaps it makes better sense to observe that all these teachers’ names appear in texts that were of primary importance to the Zhijé school, in particular the trilogy called the Gold Ball, Silver Ball and Crystal Ball. If you want to know more about these texts, look in the bibliography and look up the references for yourself if you will.

I plan to go ahead with the rest of the painting, although I’m not so sure I will put it all up here on Tibeto-logic blog. I can say that each of the groups of figures above Padampa has something to do with revealing or transmitting specific teachings that are represented in the form of texts in the Zhijé Collection.

I do think a careful consideration of the group of Tibetan students of Padampa in the lower part of the painting might have interesting implications for reconsidering the date of the painting. So maybe we’ll look at that part next time instead of moving up into the higher levels.

I do think a careful consideration of the group of Tibetan students of Padampa in the lower part of the painting might have interesting implications for reconsidering the date of the painting. So maybe we’ll look at that part next time instead of moving up into the higher levels.

§ § §

Bibliography:

Kurtis Schaeffer, Crystal Orbs and Arcane Treasuries: Tibetan Anthologies of Buddhist Tantric Songs from the Tradition of Pha Dam pa sangs rgyas, Acta Orientalia (Oslo), vol. 68 (2007), pp. 5-73. Here on pp. 20-22, you may find English translations of incipit and colophon for three texts that explicitly state that they are teachings of the “54 male and female teachers.” The same three texts may be found in the publication that follows, pp. 1-16.

Mkhas-grub Khyung-po-rnal-'byor et al., Zhi byed dang shangs pa'i chos skor, Dpal brtsegs bod yig dpe rnying zhib 'jug khang, Bod ljongs mi dmangs dpe skrun khang (Lhasa 2010). This is a small and handsome paperback volume, no. 7 in the series called Mkhyen brtse'i 'od snang, containing several of the key Zhijé texts in a nicely edited form with very clear print, making them easier to read. All of the Zhijé texts included in this book have been published previously. I mention it here because it’s inexpensive and accessible.

The Zhijé Collection, as I call it for short, is the most important available resource on Padampa and his Zhijé teachings by far (originally in 4 volumes, but published in 5). TBRC (Tibetan Buddhist Resource Center) makes it available in PDFs, which is wonderful, but they catalog it under the name Zhi byed snga bar phyi gsum gyi skor. This incorrect title implies that it includes the early and middle transmission texts of the Zhijé, when in fact it has the texts of the later transmission alone.*

To get to the Zhijé Collection, trythis link, or if that doesn’t work, try this one (http://www.tbrc.org/) and type “W23911” in their search box. In the future, if a Tibetan title for the collection is needed, I think it ought to reflect the title that is actually there on the manuscript. Although difficult to read in the reprint edition, it is more legible in the microfilm version of the text that was made independently by the Nepal-German Manuscript Preservation Project. What we find there is this: Dam chos snying po zhi byed las / rgyud phyi snyan rgyud zab khyad ma bzhugs // glang skor bzim chung phyag pe'o [~glang 'khor gzim chung phyag dpe'o].If a short title is needed, I recommend Zab khyad ma, which means [the manuscript - or the transmission it represents - called] Exceptionally Profound.

Note: No sooner had I posted this blog than I thought I have to take back my idea about calling the entire Zhijé Collection under the name Zab khyad ma. Actually, although it only appears in the microfilm of the text (like so many other things, actually), there is a colophon at the end of the first volume (ka) of the original manuscript that brings the Zab khyad ma to an end. In other words, this title only applies to the teachings of Padampa and his Indian teachers, and not to the responsa (zhu-lan) texts etc. of Kunga and later members of the lineage that fill up the rest of the collection (and the greater bulk of it). Another point that may seem small, the information in this colophon applies only to the first volume, and ought to be understood as a copying of an earlier (now ‘lost’) textual entity that had the same content as the first volume... OK, enough of that for now.

(*This means primarily the one transmitted by Kunga, although there were 3 other disciples of Padampa who held transmissions that are also called “later” and that had smaller text collections that have not surfaced yet, although they certainly existed in earlier times.)

To get to the Zhijé Collection, trythis link, or if that doesn’t work, try this one (http://www.tbrc.org/) and type “W23911” in their search box. In the future, if a Tibetan title for the collection is needed, I think it ought to reflect the title that is actually there on the manuscript. Although difficult to read in the reprint edition, it is more legible in the microfilm version of the text that was made independently by the Nepal-German Manuscript Preservation Project. What we find there is this: Dam chos snying po zhi byed las / rgyud phyi snyan rgyud zab khyad ma bzhugs // glang skor bzim chung phyag pe'o [~glang 'khor gzim chung phyag dpe'o].If a short title is needed, I recommend Zab khyad ma, which means [the manuscript - or the transmission it represents - called] Exceptionally Profound.

§ § §

Note: No sooner had I posted this blog than I thought I have to take back my idea about calling the entire Zhijé Collection under the name Zab khyad ma. Actually, although it only appears in the microfilm of the text (like so many other things, actually), there is a colophon at the end of the first volume (ka) of the original manuscript that brings the Zab khyad ma to an end. In other words, this title only applies to the teachings of Padampa and his Indian teachers, and not to the responsa (zhu-lan) texts etc. of Kunga and later members of the lineage that fill up the rest of the collection (and the greater bulk of it). Another point that may seem small, the information in this colophon applies only to the first volume, and ought to be understood as a copying of an earlier (now ‘lost’) textual entity that had the same content as the first volume... OK, enough of that for now.